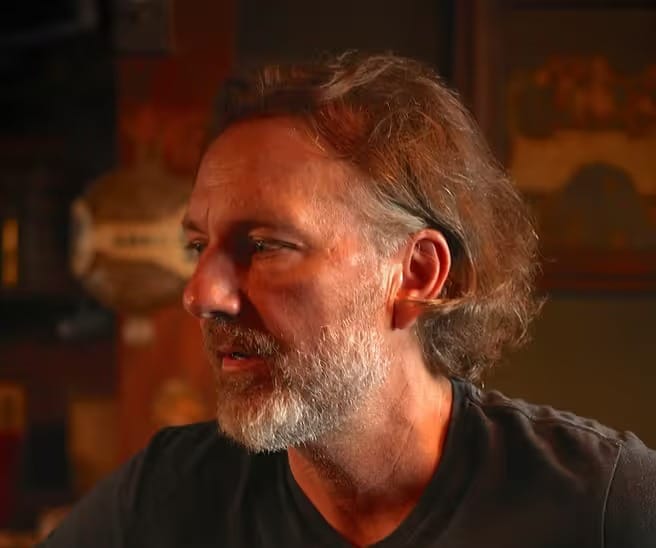

Interview: Michael Farris Smith

Michael Farris Smith is an award-winning writer whose novels have appeared on Best of the Year lists with Esquire, NPR, Southern Living, Garden & Gun, Oprah Magazine, Book Riot, and numerous other outlets, and have been named Indie Next, Barnes & Noble Discover, and Amazon Best of the Month selections. As a screenwriter, he scripted the feature-film adaptations of his novels Desperation Road and The Fighter, titled for the screen as Rumble Through the Dark. With his band The Smokes, Smith wrote and released the record Lostville, which was produced by Grammy nominee Jimbo Mathus. He lives in Oxford, Mississippi, with his wife and daughters.

Interview: Michael Farris Smith

Porchlight: In Desperation Road, you bring together Russell Gaines, newly released from prison, and Maben Jones, a formerly homeless mother on the edge, in a story of second chances and desperation. What was the core emotional question you wanted to explore through their intersection—and how did that shape the set-up of the novel from the very beginning?

Michael Farris Smith: I don’t know that I can pinpoint any singular core emotion that I was hoping to explore. It was like most things – layered. There was a search for home. A search for belonging. A search for mere survival. A search for redemption and for Russell, a search for forgiveness. That feels like a lot of different emotional questions to me. And I guess somewhere in there lies notions of fate and destiny and the vibrance of the past and past decisions. I don’t think there was ever the thought of “this is what I’m going for.” But there was the thought that this is weighted and there are plenty of questions to explore between Maben and Russell. And that’s usually a good sign that you’re on to something.

Porchlight: The Fighter opens with Jack Boucher driving toward the Mississippi Delta, an envelope of cash in the glove box and no idea how far he’s already gone wrong. You’ve said you wanted to “push him … see how far he could go and what all he could endure.” In what ways did you let Jack’s physical deterioration (his injuries, memory problems) mirror a deeper psychological or moral decline, and how did you decide when he might reach a moment of redemption or reckoning?

MFS: Jack’s creation was born out of physical pain. The very first words I wrote to his story was a long passage where it describes everything he felt. All the fists and elbows and busted shoulders and broken teeth and so forth and so on. I think it ran for nearly a page. There was intensity and extremity in it that I loved and it occurred to me that anyone who had come to such physical pain and extremity had come through a similar experience from an emotional and spiritual standpoint. The mirror was already there. I just had to go and find those things he had endured emotionally. I always believed there would come a moment of reckoning for him, that was just the way he lived his life, though I can’t say I knew what that was until I got there.

Porchlight: With Lay Your Armor Down, you introduce a very different tone—a dark Southern gothic chase involving a messianic child, hired gunmen, and an abandoned church in the woods. What drew you to that concept of “laying your armor down” (metaphorically and literally) in this novel, and how did you build the story to reflect characters removing protective layers rather than simply defending themselves?

MFS: I was drawn to the title because of its connotation. If you are laying your armor down, that means you had it to begin with, which means you have been engaged in the battle, you have survived the battle, but there is nothing left to give, nothing to do but let the world have its way. The further I went into the story, the stronger I felt this in all of the characters of Keal, Cara, and Burdean, but in particular Burdean. He thinks he’s seen it all, but he hasn’t. Fate has brought them all to this moment of great decision, or indecision, and sometimes the only way to decide what to do is just let go and let the moment have its way. You have to lay down the armor.

Porchlight: Across several novels–your work blends visceral, physical detail with poetic, almost hymn-like prose. For example, in The Fighter you describe Jack’s body as if “every blow he had absorbed … still existed somewhere in an invisible cloud of pain.” When you’re revising, how do you decide when to stay in the sensory, physical moment and when to pull into a more lyrical or reflective register? What’s your internal gauge for language tone vs. narrative momentum?

MFS: I don’t think it has much to do with revision. Those moments always feel the most impulsive for me, the moments and language and lyricism that just arrives in the course of writing a scene or stream-of-consciousness or even something as simple as a single thought a character may have. Because of that impulsive nature, I just let it go and see what comes out of it and more times than not it lands right where I want it to be. Those are always the most engaging moments of my writing life. And it does provide a momentum to the narrative which is why I don’t think I keep a gauge on it. I’ve learned to recognize when those moments arrive and I try to give them as much freedom as they can be given. And then you can feel it when it has extinguished itself, just like you can feel it when it catches fire.

Porchlight: Many of your characters operate on the brink—legal, moral, existential. In Desperation Road, you have a deputy sheriff’s attempted rape triggering Maben’s action. How do you craft scenes of trauma or violence so that they feel truthful and that the reader remains emotionally engaged (rather than numbed or alienated)? Do you have a specific revision strategy to check for balance between realism and reader accessibility?

MFS: I think there are two ways I have always thought about it. First, there is nothing romantic about it. If there is any time to deal with realism, that is the time. Second, keep it economic. I don’t think the reader wants to live with violence that goes on and on and I also don’t think the reader needs to see every drop of blood or piece of skin or whatever else could be described in such moments. Hit the moment, hit it hard with the images that matter, and move on.

Porchlight: In revisiting your work, there’s a strong sense of place—Mississippi, the Delta, the woods and roadways, even the abandoned church in Lay Your Armor Down. How has your relationship to setting evolved from earlier novels to Lay Your Armor Down, and how do you use setting as a character or force in the story?

MFS: As far as evolution, that’s a good question. I started with Paris, then moved into a dystopian Mississippi Gulf Coast, then used my old hometown, then the Delta, then the kudzu, then WWI, and then returned back to the downtrodden landscape of pre-Rivers with Salvage This World and Lay Your Armor Down. Setting feels like a big deal all the way through, or at least it is to me. If anything, though, it’s probably gotten darker, which is where I guess the Southern Gothic moniker had emerged from.

I don’t suppose I know any other way. I was always, and still am, drawn to stories and writers who use setting as character and force. Faulkner’s Mississippi. McCarthy’s border. Hemingway’s Paris. Maybe part of the reason I love it is because of the silence. Landscape doesn’t speak. It’s just there. But so much can be delivered that way and I do crave looking for ways to tell a story where much is left unsaid. Setting does that if done the right way and it can be very impactful.

Porchlight: Looking ahead, what excites you about the future of your work—whether in terms of new themes, form, or even adaptation (since you’ve written screenplays for both Desperation Road and The Fighter)? What question or challenge are you most eager to tackle next?

MFS: I’m not sure. I have become involved in films and scripts. But I don’t know that I can wholly step away from writing a novel. There is just so much about it that is part of me. The most important thing for me, and it has always been, is that whatever I’m doing, there is a fire burning inside of me to do it and to give it as much as I can possibly give. That will always excite me.