"The Plan Room" by Eli Cranor

Nationally-bestselling, Edgar Award-winning author Eli Cranor played quarterback at every level: peewee to professional. These days, he serves as Writer in Residence at Arkansas Tech, where he also lends his expertise to the university's football team, an experience he mined while drafting Mississippi Blue 42.

The Plan Room

The way his cousin was leaned real far forward, grinning up at the broke-down building, the plywood drilled over the windows, the crumbling stone façade—Nate wasn’t sure what to make of it.

He wasn’t sure what to make of his second cousin at all. Didn’t even recognize his name right off. Cutter Jester? Sounded like a rodeo clown, talked like one too, his voice on the phone saying, “Hidy, cousin,” when he’d called direct from the Pope County Detention Center three days ago. Cutter said he was getting out on Friday and wondered if Nate could pick him up. Hadn’t seen him in, what, five years? Nate halfway remembered that one Thanksgiving at Mamaw’s place, her rickety old house on Front Street back before it burned down, Nate nine at the time, Cutter a little older, ten or twelve, not a single pimple or pube between them. Come to think of it, that might’ve been the only time Nate had ever been around his second cousin Cutter.

Sitting in the passenger seat of Nate’s ’98 Ford Bronco, Cutter pressed a finger to the glass, pointing at the dilapidated building across the street. Nate knew the neighborhood. A few old friends lived in apartments a block or so away.

“Thanks for the ride, cousin. I can handle it from here.”

Cutter rocked back then forward, readying himself to exit the Bronco, but Nate said, “Hold up. You just got out, man. Sure you wanna go in there?”

“It’s a school, cousin. Ain’t nothing to be scared of.”

“There’s kids in there?”

“Holds sixty, but only ten or fifteen show up most days.”

“How many teachers?”

Cutter’s eyes went up in his head. “Five. Plus a principal, counselor, secretary, janitor, and this crotchety old bastard named Leo runs the Plan Room.”

“The what?”

“The Plan Room. That’s where they keep the bad kids.” Cutter grinned over his shoulder. His teeth were straighter and whiter than Nate had expected. “Whole school’s full of bad kids, but the Plan Room? Shit. That place made the Pope County DC feel like church camp.”

“You went there?” Nate said. “That’s where you went to high school?”

“Little bit of junior high, too. Right after I slapped the shit out of Mr. Fruehauf. Remember him?”

“The principal?”

“Yeah, real big guy with horse teeth, always had on them gator skin boots with the three-inch heels. Had to duck a little and turn sideways when he walked in a classroom. Think he made the practice squad for the Cowboys but got cut real quick. Bad knees or some shit.”

Nate remembered Mr. Fruehauf. “You slapped him?”

Told me I’s gonna have to clean the boys’ toilets for a whole damn week. Thought I’d pinched a loaf in the urinal but I didn’t. Shit. I couldn’t. I’ve always had trouble with my bowels. Tried telling Mr. Fruehauf that,” Cutter said, shoulders hunched forward beneath his fur-collared, Sherpa jacket. Looked homemade to Nate, like a fox’s hide wrapped around his cousin’s neck, or maybe just a bunch of squirrels. “Tried telling him my ass was plugged up thicker than Quikrete. Said that line straight to his face, word for word.”

A voice inside Nate Dalton’s head told him to leave it be. He knew what his cousin was doing, sitting there, waiting for Nate to ask how Cutter wound up slapping the shit out of Mr. Fruehauf. Did he have to jump? That principal was real damn tall. There were a hundred other questions, but Nate knew better. He didn’t need any trouble. He’d just moved out. Left his momma and them in the that trailer across the river in Dardanelle. Nate had a job at Conagra now, and girlfriend called herself “Blake.”

Things were lining up, finally working out. Nate flexed his fingers over the Bronco’s steering wheel, memories of cousin Cutter coming back to him, stories Nate had overheard through the Skyline doublewide’s poorly insulated walls, his momma whispering to The Sisters about Aunt Velma’s daughter Lucy’s boy. Cutter Wayne Jester would’ve graduated from Russellville High School in 2017. Would’ve gotten to walk across the stage, shake hands with Mr. Fruehauf and everything. Didn’t matter one bit he’d spent 9th-12th grade in that big stone building across the street. The place didn’t have any windows. Made Nate feel real bad for his second cousin, trapped in there all those years. Bad enough he said:

“And then what?” regretting it the moment Cutter turned back to him and grinned, two sharp eye teeth on full display. “I told you the end of that story already, baby cousin. Mr. Fruehauf sent me to rot in that hell hole over yonder for slapping the shit out of him. He was sitting behind his desk when I done it. Otherwise, I would’ve had to jump.” Cutter’s black eyes danced crazy eights under bushy blond brows. “You know the point of that story, Nate?”

Nate thought, No, but didn’t say anything.

“Point is, I never cleaned no fucking toilets.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The kids sat in cubicles facing the walls, eight hours a day, every day until they served their time. Got two bathroom breaks. One before lunch. One after. Couldn’t talk at all.

One word and Leo Miller would put his book down, write the kid’s name on the whiteboard behind his desk. Two words—that kid went home, came back the next day, and every day after, until his suspension was over.

In-School Suspension.

Leo loved it. Got paid a teacher’s salary—sick days, health insurance, retirement, the works—just to sit there and bust some kids’ balls. Didn’t have to teach them anything. Leo’d done enough of that already. He’d served his time. Twenty straight years of sophomore English at North Little Rock High, getting cussed out and tripped in the halls. Oh yeah, he could sit back and relax for a while. Prop his feet up and read the Louis L’Amour paperbacks he’d found in his father’s office when he first moved home.

The sound of lake water lapping had calmed Leo’s nerves, washed away all those years he’d spent in the city. He hated leaving the lake each morning but was always excited to come home. Seventeen years of a slow, peaceful life, enough time, enough distance, Leo was finally ready to write a book of his own.

A yellow legal pad with two words scribbled in blue ink at the top of the page—the product of Leo’s first hour of work. The words had been crossed out. It was harder than he’d imagined. Louis made it look so easy. And Leo wasn’t even making anything up; he was just remembering, or at least trying to remember all the wild stories from his thirty-seven years spent in public education. Leo didn’t have any children, or a wife, but someday someone would buy the lake house, for the view, if nothing else. Maybe they’d find his stories, the same way he’d found his father’s collection of dime-store paperbacks.

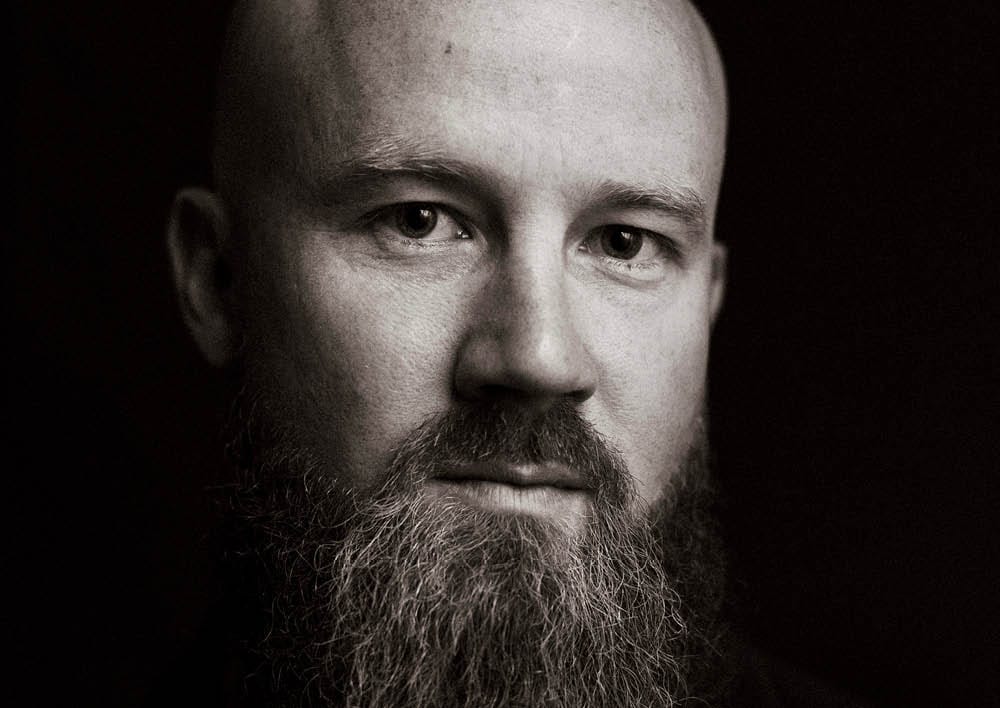

Leo pressed his pen to the paper and watched the ink bleed out, a blue cloud expanding over yellow, making the sixty-one-year-old think of the lake again, the fog in the morning. Leo stroked the beard he’d been growing in preparation for retirement, trying like hell to think of an opening line. Something. Anything to get him going. There were all sorts of stories from the early days, knife fights and kids fucking in the bathrooms, under the bleachers, the back corner of the library. You name it.

But that wasn’t what Leo wanted to write about. He needed a character. A student who stood out amongst the others. A boy. Yes. Extra squirrelly. He could almost see him now. With a funny name. Sounded like something from a Louis L’Amour novel. What was it?

The inkblot was quarter sized by the time the name came to Leo. He lifted his pen from the paper, finally ready to write, ready to try and get that boy out of his head on the page, when a high-pitched siren erupted from the hallway, followed by flashing lights.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cutter pulled the fire alarm and ran.

Nate just stood there and watched it happen. He’d followed his cousin into the school building without knowing why. Same way he’d gone to pick him up from the DC. Like Cutter’d cast a spell on him.

When the first door opened and the kids started pouring into the hall, all that was left of Cutter were black marks from his boots on the linoleum floors. An image of a broomstick with a tennis ball stuck on one end popped into Nate’s mind; Mr. Jimmy the stringy-haired janitor from his elementary school lugging that stick around, scrubbing at the scuff marks every afternoon. Mr. Jimmy had buckteeth and barely any eyebrows. A face that was hard to forget. Same face as half the kids in the hallway now.

That fire alarm was still going off. A sharp, pulsing sound that reminded Nate of a dog whistle with a strobe light that flashed every other second.

And the kids—the “students”—they were headed Nate’s way. Coming straight for him. A mob of graphic tees, neon green hair, and septum rings. Couldn’t tell the girls from the boys. They all had love handles and acne. More than half were wearing glasses too, the lenses smudged like the windows in the Waffle House on West Main.

The students streamed past Nate without so much as a word or a sideways glance. They didn’t see him standing right there by the fire alarm, couldn’t see him, not with their eyes glued to the glowing screens in their hands, highlighting their scarred cheeks and sterling silver appendages. They smelled bad too. Stale cigarettes and ass with a little chemical aftertaste. Cherry, or maybe grape? Nate guessed whatever it was came from a vape and held his breath until the herd had passed.

With the hallway finally cleared, Cutter’s black boot marks marked a path to freedom, one Nate planned to follow all the way up until the first teacher waddled out of the lounge, followed by another one about the same size. Pushing two-hundred pounds. Both of them. All of them. There were four now. Eight hundred pounds of great white teacher flesh rippling its way toward Nate and that still-engaged fire alarm. Shoulder to shoulder, they’d formed a wall, a wrecking ball, ready to bowl Nate over, bulldoze his skinny ass straight out the front doors all the way into the back of a police cruiser.

Their stench was somehow worse than the kids, something like Sweet ‘N Sour Chicken left in the car a couple hours too long. Nate couldn’t even hold his breath this time. It was too late. All he could do was press his back to the wall, close his eyes, and wait for the end.

Nate’s back never touched the wall.

In fact, there wasn’t a wall behind him at all. There was a door, which opened just as the teachers stomped by. There was a hand on Nate’s wrist too, yanking him inside then easing the door shut behind him.

The man let go of Nate’s wrist and said, “I know you.”

He was bald and dressed like a lumberjack. Like an old teacher who wanted to be a lumberjack. What was that movie Nate’s dad liked so much? Jeremiah Johnson. Yeah. This guy looked like the bald guy from that movie, the one with the mustache gets buried up to his neck and left to die by some Flathead Indians, or maybe they were Crow. Nate couldn’t remember.

The alarm was background noise now. The flashing lights in the hallway hidden behind the closed door.

“Yeah . . .” The teacher chewed the word and wagged a finger in Nate’s general direction. “I never forget a face. Names? Now, that’s different. Kids come up to me in Walmart, former students, stand in front of my cart and grin, waiting for me to say, ‘Hi, Stevie,’ or ‘Lucy’ or these days, Jesus, it’s more like ‘Hi, Trashuan.’ You believe it? Had a ‘Dharma’ last semester, and another named ‘Chevylynn.’ All one word squished together like that.”

“My name’s Nate.”

“Nate?”

“Yeah. Just Nate.”

The man placed a finger on his chin. “Have you been suspended?”

Nate started to shake his head but stopped.

“You pulled that alarm, didn’t you?”

Nate heard the alarm now, loud and clear, that damn dog whistle going off like a bomb inside his head. “I didn’t do shit, mister.”

The bald man frowned and took Nate by the wrist again, jerking him back out of the door. The strobe light flickered across an empty hallway. A siren wailed somewhere beyond the rock wall and the plywood. Nate hoped it was a firetruck but knew better.

The hell had just happened? He’d gone to get his cousin out of jail less than an hour ago, and now the cops were coming. That’s how bad shit went down. Quick. The same way Cutter appeared in the hall again, standing at the far end with what looked like a fire extinguisher in both hands.

“Mr. Miller?” Cutter waited a second then hollered, “You remember me?”

“Cutter.” The man licked his pale lips. “Cutter Wayne Jester.”

Damn. Even had Cutter’s middle name down pat. Nate knew his cousin well enough to know he left a mark on people. An impression. What he didn’t know was what in the hell Cutter planned to do with that fire extinguisher.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Last thing the kid told him—what was it, almost three years ago?—was that he’d come back and “burn the motherfucker down.”

Leo didn’t get it. Not then. Not now. If Cutter wanted to “burn” the school down, why had he pulled the fire alarm? And what was he doing standing there with that big red extinguisher?

There were no answers. Not when it came to kids like Cutter. There was only pain, a long line of it, extending all the way back to the Stone Age, or maybe the Mesozoic Era, whenever cavemen first started roaming around. That’s when boys like Cutter had emerged, when they’d thrived, chasing five-ton mastodons down and killing the beasts with spears. The mastodons were long gone, their bones on display in museums Leo hoped to visit after he’d retired, but the Cutters of the world remained, wreaking havoc on obese teachers before giving the local PD hell. That was Cutter Wayne Jester’s lot in life, the path that had led him here.

“You remember what I told you?” Cutter had his legs spread, bracing himself under the bulk of that fire extinguisher. The boy didn’t weigh a buck fifty, too much raw energy packed in tight, a gift from his knuckle-dragging bloodline, metabolizing all those Big Macs and countless packs of Ramen Noodles.

“You remember what I said?”

Leo remembered. It was the first thing he’d thought as soon as he’d seen the boy, that promise he’d made on his final day in the Plan Room. Leo didn’t tell Cutter that, though. He didn’t want to give him the satisfaction. He wanted to see the kid in the back of a squad car, head bowed, both wrists handcuffed behind him. Yes. That’s what Leo wanted, and that’s exactly what would happen if he could just keep the dumbass talking, gabbing on about what he was gonna do before he went and did it.

“Said’s I’s gonna burn this motherfucker down!”

The other boy in the hallway winced. Leo had forgotten about him. What’d he say his name was? Nate? Cutter’s partner in crime—that’s who Nate was, probably his half-brother, or maybe, on second thought, a cousin of some sort. This kid lacked Cutter’s feral eyes and looked even lighter in the britches.

“Yeah, buddy,” Cutter said and started forward, patting the extinguisher, playing with it as the fire alarm cut off mid beep. “Already got it all set up.”

Leo took the bait. He couldn’t help it. “What do you have set up, Cutter?”

The boy’s teeth glistened in the still flashing lights, there for a moment then gone. “Bomb. Pipe bomb. Made it myself. Fifty artillery shells stuffed way down deep in some PVC. This whole place’s about to go up like the Fourth of July.”

Leo thought about letting the boy get close enough he could wrench the fire extinguisher from his hands. He saw himself doing it in his mind. The setting was different, though, the school replaced by an old Western saloon, a scene out of the book he’d been reading. That’s all that was, but this was real life, as real as it got.

“Artillery shells?” the other boy said. “Like, fireworks? That’s what you got in there?”

“Yeah.” Cutter nodded two times, quick. “I stuck it in the toilet.”

Leo took a step back watching as the other boy—Nate—bellied up to the crazy one. “This whole place is made of cinderblocks. That’s concrete, Cutter. The hell you think a bunch of firecrackers gonna do?”

“Artillery shells, cousin.”

Leo grinned to himself. He’d called it.

“Hundred-gram load,” Cutter continued. “The good stuff.”

“Hundred grams, huh?” Nate ran a hand over his face. “You hear them sirens, man?”

Cutter looked first to the now silent fire alarm mounted high on the wall, then to the glass doors that faced the highway, the same doors Leo guessed the boys had walked through only minutes before.

“Yeah, I hear them,” Cutter said. “So?”

“Them the cops, man, and if we don’t get the fuck out of here, you’re going right back in the DC, except this time—” the cousin swiped at his face again “—this time, I’ll be in there with you.”

Cutter’s shoulders fell forward beneath his coat’s fur-lined collar. The fire extinguisher sagged in his hands.

“Just go get it out of the toilet,” Leo said, lacing his fingertips at his waist, a tactic he’d learned during professional development, a way to put the students at ease. “Then y’all run. Take off and get the heck out of Dodge.”

The boys straightened, staring back at him without blinking.

“When the police arrive, I won’t say a word. You were never here.”

A siren yipped, louder and closer than before. A car door slammed. The cousin nodded.

“Then go!” Leo shouted, employing his teacher voice, the same voice he used to rule over the Plan Room. “What are you waiting for?”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The teacher’s voice was still echoing down the hall when Nate heard the low boom and turned. The sound of Cutter’s pipe bomb was short-lived, erased by the sharp thwack of that fire extinguisher connecting flush with the old man’s nose.

Blood ran in thick red lines through the teacher’s white beard. Reminded Nate of Christmas. He watched the memory float by and fought to hold onto it, fought to remember the exact moment he’d stopped believing in Santa Claus, if he ever had at all.

The old man went down on one knee and Cutter hit him again, in the chin this time, using the extinguisher like a battering ram. The teacher fell flat on his back, arms straight out at both sides.

There was smoke on the ceiling now, great plumes of it, and blood on the floor. Cutter stepped forward, wedging the toes of both boots beneath the man’s armpits, straddling him as he hefted that bright red fire extinguisher into the smoke.

Why?

That was the question Nate should’ve asked, the only one he could think of, but way back in third grade Ms. Mashburn—a teacher the same size as the ones who’d just stampeded down the hall—had told him not to ask stupid questions. Really ripped Nate a new one because he’d been genuinely confused about the past tense of some word he couldn’t remember now, but damn if that big woman hadn’t taught him something.

By the time the first cop came through the door, Nate was already gone, running out the cafeteria exit for those apartments where he still knew a few guys, boys he’d gone to school with, men who were grown now and had jobs and girlfriends—a couple probably had kids—but they’d understand. They’d take Nate in if he asked, and that’s just what he was going to do.